Eastern Coyote

Some facts about eastern coyotes may surprise you. These beautiful animals are actually a hybrid between western coyotes (Canis latrans) and eastern wolves (Canis lycaon). They are morphologically and genetically unique and different from both of their parent species. They now live throughout Northeastern North America and have replaced the original 60-70 pound eastern wolf that originally lived here. Due to their hybrid background, published research also supports the nomenclature “coywolf” (Way et al. 2010, Way 2013). Eastern coyotes may live as solitary individuals, in pairs, or in small family groups, both in rural and urban areas. However, in areas where people do not kill them, the dominant social system is for them to live in small packs of 3 to 4 adults that raise pups each spring and guard a territory from other coyotes. They are monogamous, and both parents work to raise the pups, by teaching their young to hunt natural prey (such as mice, rabbits, and woodchucks) and to avoid dangers such as people and cars.

Some people believe that there is a coyote overpopulation problem, or that they are seen everywhere. They actually exist in much smaller populations then most people believe. Both male and female coyotes actively maintain their territories that may vary in size from 2 to 30 square miles but average 5-10 square miles in MA. Coyotes travel long distances even during the course of one evening. Thus one pack may be seen in one location one day and miles away the next, making their presence seemingly larger than it actually is. Their territoriality naturally inhibits overpopulation. Other factors that limit populations are disease, prey base, habitat and human hunting. Furthermore, reproduction is once per year and limited to the group’s leaders (called breeders or alphas). Breeding season occurs in January/February, followed by 4-8 pups born in a den in March or April. Pup mortality is often high. Some juveniles disperse in late fall to seek new territory, while some individuals remain with their parents and form a pack (Way et al. 2002).

Whether alone or in a pack, eastern coyotes are naturally shy and reclusive. These animals are known to travel at night to avoid interactions with humans (Way et al. 2004). Humans only need to take simple precautions to prevent and minimize any potential conflicts. These precautions will protect you and the wild animals that live among us.

Eastern Coyote Checklist of Facts:

General Description of the Eastern Coyote or Coywolf

- Lives in all of the northeast from New Jersey to Maine; western coyotes live in the reminder of the country outside of Northeastern North America.

- The biggest type of coyote – 30-45 lb. on average

- Track size is oval and from 3-3.5 inches long

- Color ranges from blonde to darker black and brown, but is usually tawny brown

Eastern Coyote Facts

- Feeds mostly on small mammals

- Opportunistic predators – eating everything from fruit to meat

- Medium sized prey is main food source: mice, voles, rabbits, woodchucks, and deer fawns

- Larger mammals where available (like adult deer)

- Habitat: Rural (wilderness) to urban

- Prefers edge habitat where different cover types meet

- Agricultural and suburban areas are perfect habitat because of this

- Edge habitat provides cover and high prey number

- Lives in 49 of 50 U.S. states and everywhere except Long Island and offshore island.

Are Coyotes Dangerous? Keep it in Perspective: Coyotes vs. Dogs (CDC data)

- 4.7 million dog bites per year in U.S.

- 800,000 people need medical attention

- 1,000 people per day go to ER

- 15-20 people, on average, die per year

- 4-5 coyote bites in Massachusetts’ history

- 2 or 3 were rabid

- 2 fatalities in recorded history in N.A. in past 500 years: one on a toddler in Cali in early 1980s (food habituated animal) and one on an 18 year old lady in Nova Scotia in 2009

- Dog bite losses exceed $1 billion per year

- $345 million paid by insurance

For more information on coyote and coywolves visit Eastern Coyote/Coywolf Research at http://www.easterncoyoteresearch.com and Project Coyote at http://www.projectcoyote.org

Grey and Red Fox

Text adapted from the Commonwealth of MA Fish and Wildlife website (http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/wildlife/living/pdf/living_with_foxes.pdf)

Foxes are members of the dog family Canidae, and their general appearance is similar to that of domestic dogs and coyotes. The red fox and gray fox are both common and abundant species in Massachusetts. Both species are found throughout the state, except on Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. Foxes prefer landscapes of mixed habitat, and thrive in areas where different habitats — forests, fields, orchards and brush lands — blend together. Foxes typically use the transitional areas between these habitat types for most of their activities.

The red fox, Vulpes vulpes, measures 22 to 32 inches in head and body length, while its bushy tail adds another 14” to 16” in total length. Adults weigh from 6 to 15 pounds, but appear heavier than they actually are. The red fox is usually recognized by its reddish coat and black “leg-stockings.” Red is the most common dominant color, but the coat, up to 3 or 4 inches long, may vary from light yellow to a deep auburn red to a frosted black. The white tip on the tail will distinguish this fox from any other species at any age.

The gray (or grey) fox, Urocyon cinereoargenteus, is often confused with the red fox because of the rusty-red fur on its ears, ruffs and neck. The overall coloration is gray, with the darkest color extending in a suggested stripe along the top of the back down to the end of the tail. The belly, throat, and chest areas are whitish in color.

The gray fox appears smaller than the red fox, but the shorter leg length and stockier body are deceptive. Many gray foxes weigh about the same as red foxes living in similar habitat types. On average, males and females weigh 8 to 11 pounds, and are generally on the heavier end of that range in this part of the country. Compared to the red fox, the gray has a shorter muzzle and shorter ears, which are usually held erect and pointed forward. Gray foxes stand about 15 inches tall at the shoulders and average 40-44 inches in length, including a tail of 12 to 15 inches. While both foxes have some cat-like features that reflect their evolution as small mammal predators (including elliptical pupils for night vision enhancement), the gray fox is the only fox that climbs trees.

Life history: Both species of foxes breed mid January to late February and begin to prepare dens during this time. A den is typically a burrow in the earth, 15 to 20 feet long, and usually located on the side of a knoll, but foxes may also set up dens in or under outbuildings, in rock crevices, or, in the case of the gray, even in trees! Dens may have several entrances. Sometimes foxes dig their own dens, but more often they appropriate and enlarge the tunnels of small burrowing animals such as woodchucks and skunks.

The single, annual litter is born after a gestation period of 53 days. A litter of 4 pups is common. The young leave the den for the first time about a month after birth. The mother gradually weans them, and by 3 months of age, they are learning to hunt on their own. Foxes are quite vocal, having a large repertoire of howls, barks, and whines. The family unit endures until autumn, at which time it breaks up and each animal becomes independent.

Foxes are usually shy and wary, but they are also curious. Activity is variable; foxes may be active night or day, and sightings at dusk or dawn are common. They remain active all year and do not hibernate. Foxes actively maintain territories that may vary in size from 2 to 7 square miles. Territories are shared by mated pairs and their immature pups, but are actively defended from non-related foxes.

Both the red fox and gray fox are omnivorous. They are opportunistic feeders and their primary foods include small rodents, squirrels, rabbits, birds, eggs, insects, vegetation, fruit and carrion. Foxes cache excess food when the hunting/foraging is good. They return to these storage sites and have been observed digging up a cache, inspecting it, and reburying it in another spot

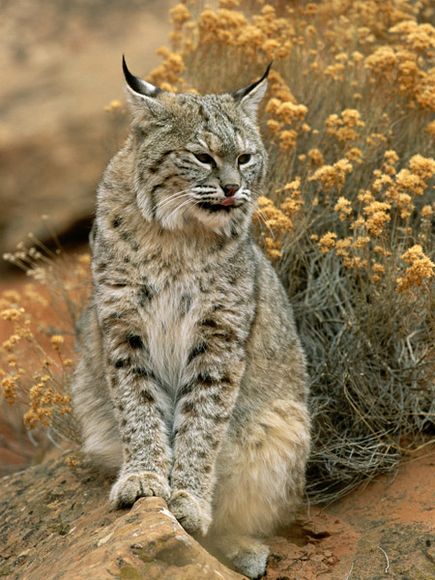

Bobcat

Text adapted from the Commonwealth of MA Fish and Wildlife website

http://www.mass.gov/dfwele/dfw/wildlife/living/living_with_bobcats.htm

Bobcats (Lynx rufus) are Massachusetts’ only wild cats since cougars (mountain lions) were exterminated in colonial days. Like many predators, the bobcat was treated as a varmint with bounties paid to kill them. Hunting of bobcats was legal year round until 1968. In 1969, Massachusetts was the first state in the northeast to reclassify the bobcat as a game animal for which a regulated hunting season was established in 1971. Still, despite better protections then the coyote or red or grey fox, there is no quota for how many bobcats may be hunted or killed during an almost 3 month hunting season. The prior quota of 50 was removed by the state of MA in 2009 at the urging of the hunting and trapping community. Thus there is no protection from overhunting and no real scientific method for determining the population. Bobcats are hunted for their fur, as trophies, and for fun.

Like most carnivores bobcats are shy, solitary, and generally elusive animals. Although they are generally silent, bobcats have a large repertoire of noises that they can produce. When confronted by an enemy, a bobcat may scowl, snarl, and spit during the breeding season they may also be heard screaming from time to time. Bobcats maintain well-defined home ranges that vary in size depending on prey abundance, season, climate, and the sex of the individual. Male bobcats maintain larger home ranges than females and it is not uncommon for individual animals to travel up to four miles daily. Both male and female bobcats use scent marking to mark well-used trails and den sites. Their use of scent is thought to help individual animals avoid direct contact with each other as they move within their home ranges. Bobcats can be active day or night but tend to exhibit crepuscular (dawn and dusk) activity. Their activity peaks three hours before sunset until midnight and again between one hour before and four hours after sunrise. They remain active year round and do not hibernate. Bobcats are proficient climbers and will climb trees to rest, chase prey, or escape from predators (chiefly domestic dogs). Like domestic cats, bobcats try to avoid water whenever possible but when forced to flee to water they can swim quite well. Bobcats are well adapted to a wide variety of habitat types. They can be found using mountainous areas with rocky ledges, hardwood forests, swamps, bogs, and brushy areas close to fields. Bobcats are well capable of dealing with human influences but tend to avoid areas with extensive agriculturally cleared lands that eliminate other habitat types. Bobcats can be classified as common in central and western Massachusetts, present in northeastern Massachusetts, and rare to absent in southeastern Massachusetts. It is thought that one of the limiting factors to bobcat expansion is the absence of suitable rocky ledges that provide cover and den sites.

Bobcats hunt by stalking (creeping from cover to cover) prey until they are close enough to pounce or they may wait on a trail or in a tree to ambush prey as it passes by. They may also run down their prey over short distances. Although bobcats have a fairly good sense of smell, they rely primarily on their keen eyesight and hearing to detect both prey and danger. They most commonly prey on medium sized animals such as rabbits and hares but will eat mice, squirrels, skunk, opossum, muskrat, birds, snakes, and other available items. Occasionally bobcats will prey upon larger animals such as deer but this is generally when other food items are scarce and only sick, injured, young or very old animals are likely to be killed. When food is plentiful, bobcats will cache the excess by covering it with leaves, grass or snow and return to feed off of it repeatedly.